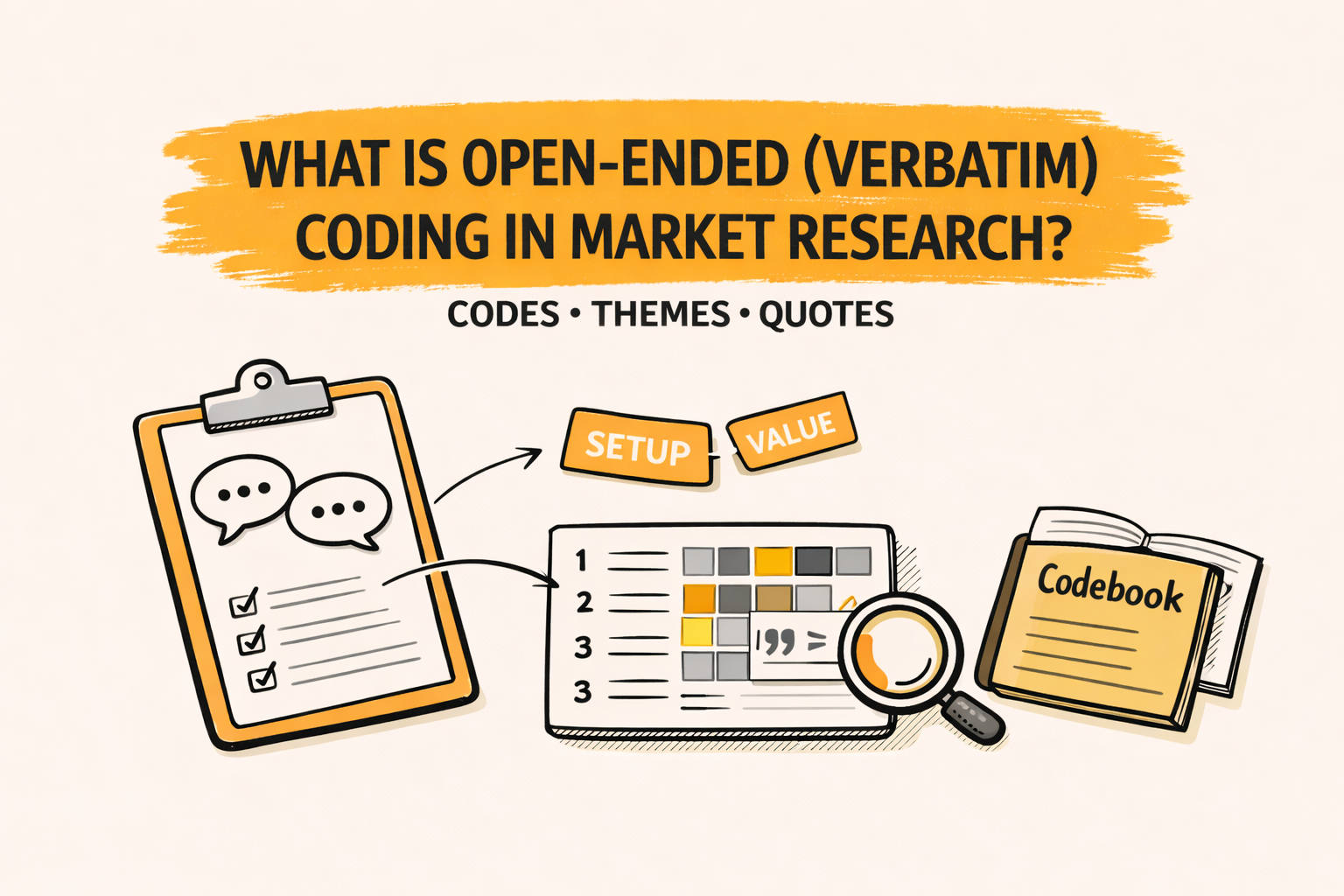

Open-ended (verbatim) coding is the process of turning free-text answers into consistent labels called codes. Those codes make messy language easier to summarize, compare, and report without losing the respondent’s voice.

In market research, coding is how teams transform verbatims into decision-ready evidence. It supports theme summaries, segment comparisons, and quote-backed reporting that can be checked and defended.

Key takeaways

- Open-ended coding converts verbatims into structured codes and themes.

- A codebook is the main control for consistency and reliability.

- Coding supports counting, cross-tabs, and segment comparisons.

- Quotes keep findings grounded and easy to verify.

- Quality improves with review, agreement checks, and clear definitions.

Understanding open-ended and verbatim data

What “open-ended” means in surveys

An open-ended question lets people answer in their own words instead of choosing from fixed options. The benefit is richer detail, better language for messaging, and clearer “why” behind ratings or choices.

Open-ended items often appear after scales, like NPS follow-ups, satisfaction surveys, and concept tests. They also show up in “Other, please specify” fields that reveal edge cases and unmet needs.

What “verbatim” means in research work

“Verbatim” refers to the raw text as it was written or spoken, with minimal alteration. In survey research, verbatims are usually short, while interview verbatims can be long and contextual.

Verbatims matter because they show how people frame problems in their own language. That language can guide product fixes, experience design, and communication choices more directly than a score can.

Why verbatims become hard at scale

A small set of verbatims can be read and summarized by hand. At thousands of responses, patterns become harder to see, and selective memory can take over.

Coding adds structure so patterns are visible and repeatable. It helps the analysis move from “a few memorable quotes” to “a consistent summary of what many people said.”

What open-ended coding produces

Codes as the building blocks

A code is a short label applied to text to capture what it is about. Examples include “price too high,” “setup confusing,” or “slow delivery.” Codes can be broad or specific, but they should be clear and reusable.

Codes make text searchable and groupable. They also create a consistent vocabulary that lets multiple people analyze the same dataset without reinventing categories each time.

Codebooks and codeframes

A codebook (also called a codeframe) is the definition set for codes. It explains what each code means, what counts as a match, and what does not count.

A strong codebook is more than a list of labels. It is the main quality tool, because it reduces ambiguity and helps coders handle edge cases in a consistent way.

Themes that tell a story

Themes sit above codes. A theme might be “Value concerns block trial,” supported by codes such as “too expensive,” “not worth it,” and “hidden fees.” Themes translate categories into insight language a stakeholder can use.

Themes should connect to a decision. If a theme cannot drive an action, it may be too vague, too narrow, or not aligned to the research goal.

Quote-backed evidence

Quotes make coded insights credible. A chart can show frequency, but quotes show what respondents meant, how they phrased it, and what nuance was present.

Quote-backed reporting also supports auditability. It becomes easier to verify the finding because the reader can see real verbatims that match each theme.

Core concepts that shape coding quality

Descriptive vs interpretive codes

Descriptive codes name what the respondent explicitly mentions, like “delivery delay.” Interpretive codes capture meaning that may be implied, like “trust issue” or “feels risky.”

Descriptive coding tends to be more consistent across coders. Interpretive coding can add value when done carefully, but it needs tighter definitions and more examples to avoid drifting into personal interpretation.

Inductive vs deductive coding

Inductive coding means codes emerge from the dataset. It fits exploratory studies, where the goal is to discover unknown drivers and language patterns.

Deductive coding starts with a predefined codebook, often from a framework or prior wave. It fits tracking work where comparability matters, and stakeholders want stable categories over time.

The “unit of meaning”

Coding requires a decision about what gets tagged. Some teams code at the response level, giving each verbatim one main code. Others code at the idea level, allowing multiple codes if multiple topics appear.

The choice should match the reporting goal. If leadership needs top reasons, one main code may be fine. If product owners need diagnosis, multi-coding often captures reality better.

Multi-coding and hierarchy

Multi-coding assigns more than one code to the same response. It is common because people often praise one thing and criticize another in the same comment.

Hierarchy helps keep multi-coding usable. A top-level code can capture the broad area, while subcodes capture detail. This supports both executive summaries and deeper drill-downs without exploding the code list.

Entities and attributes

Some projects separate “topics” from “entities.” A topic code might be “support response time,” while an entity tag might capture “chat,” “email,” or a product module name.

Attribute tagging also helps, like “new customer” or “renewal stage,” when that information is present in text. This can strengthen segmentation when structured fields are missing or incomplete.

If you’re choosing a survey open-ends coding tool, look for one that supports all of the above: descriptive + interpretive coding, inductive + deductive workflows, response- and idea-level tagging, multi-coding with hierarchies, and entity/attribute tagging. A popular option in this space is BTInsights, built to support these types of verbatim coding needs and use cases.

Reliability, validation, and bias controls

Consistency is the practical goal

Coding is rarely perfect, because language is messy. The practical goal is consistency: would another trained coder apply the same codes and produce the same top themes?

Consistency improves when code definitions are concrete and examples are clear. It drops when codes are vague, overlapping, or based on judgments like “bad experience” without specifying what “bad” refers to.

Inter-coder agreement in simple terms

Inter-coder agreement compares how two or more coders label the same sample of verbatims. High agreement suggests the codebook is clear and the rules are workable.

When agreement is low, the fix is usually in the codebook, not the coders. Overlapping definitions, missing examples, and unclear boundaries are common causes of disagreement.

Bias risks to watch

Bias can appear when coders overfocus on vivid stories or interpret ambiguous text in ways that match expectations. It can also show up when coders assume intent that the respondent did not express.

Bias controls are concrete habits. Clear rules, documented decisions, and reviews of disputed cases reduce the influence of any single person’s interpretation.

Audit trails and traceability

Traceability means a reported theme can be linked back to the underlying verbatims. An audit trail captures codebook versions, rule changes, and how hard cases were handled.

These practices matter when results are challenged. A team can point to definitions, show representative quotes, and explain how the dataset was classified without relying on memory or intuition.

How coded verbatims become “data”

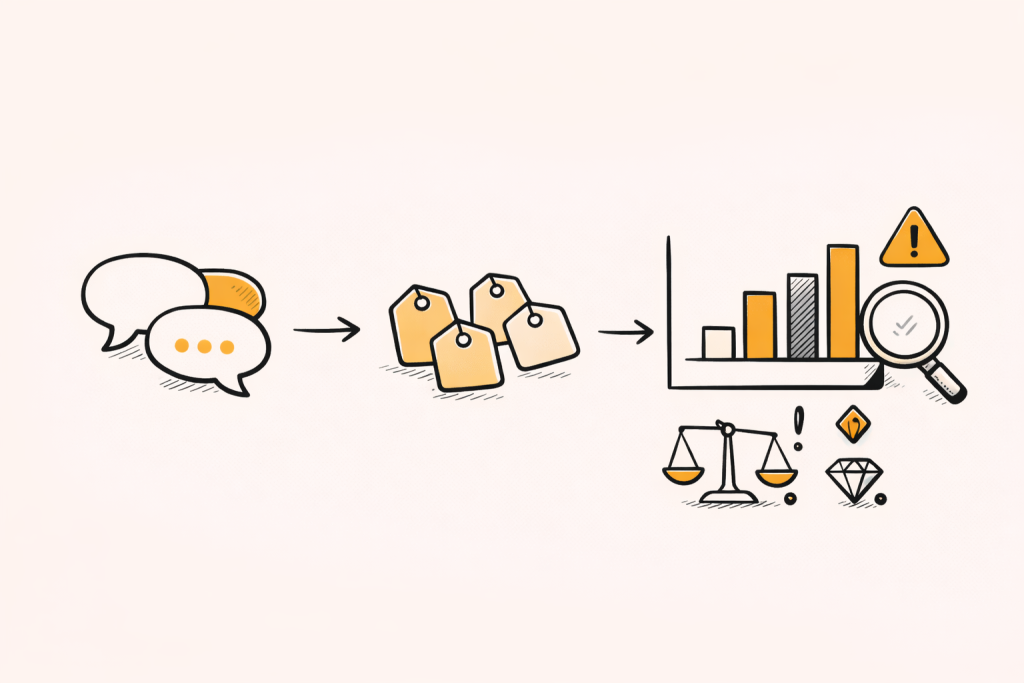

Turning text into counts

Once coded, text can be summarized with frequency tables. This answers questions like “What issues are mentioned most?” and “Which benefits are most common?”

Counts should be interpreted carefully. A frequent theme can be low impact, and a rare theme can be high risk. Frequency is a prioritization clue, not a full measure of importance.

Cross-tabs and segment comparisons

Coding becomes especially valuable when paired with segments. Codes can be compared across region, plan type, tenure, or satisfaction group to identify differences in drivers.

This is where open ends often outperform closed-ended lists. Respondents surface new topics, then coding makes those topics comparable across groups without forcing the team to guess categories upfront.

Trend tracking across waves

Tracking requires stable categories. If codes shift too much, trend lines become hard to trust because the “same” code no longer means the same thing.

Stable top-level codes with flexible subcodes often work well. The top layer stays comparable, while subcodes capture new language and emerging issues without breaking the trend story.

Linking verbatims to structured outcomes

Open ends are often paired with metrics like satisfaction, preference, or likelihood to recommend. Coding can reveal which themes show up more often among low scorers versus high scorers.

This supports driver narratives, even if it does not prove causation. The value is practical: it highlights where to investigate and what to fix first.

Open-ended coding versus sentiment analysis

Different questions, different outputs

Sentiment analysis labels text as positive, negative, or neutral. Open-ended coding labels what the text is about, such as pricing, onboarding, or support.

They can work together, but they are not substitutes. “Negative” is not actionable until the topic and context are known, and a topic alone may miss whether the response is praise or complaint.

Mixed sentiment is common

Many verbatims are mixed. A respondent might love the product but dislike the billing model, or praise speed but criticize reliability.

Topic coding helps separate those ideas. When paired with sentiment or polarity tags, it can show which topics are driving dissatisfaction versus delight within the same dataset.

What “good” reporting looks like

Balancing summary with proof

A good report makes a clear claim, shows how common it is, and provides quotes that represent the theme. It avoids selecting only extreme quotes that create drama but misrepresent the typical experience.

The goal is credibility. Stakeholders should be able to read the quotes and agree that the theme matches what respondents actually said.

Frequency, severity, and opportunity

Frequency helps prioritize, but severity changes the decision. A small number of safety or trust concerns can outweigh a larger number of minor usability complaints.

Opportunity framing also matters. A theme can indicate a fix, a positioning angle, or a segment-level play. Coding supports opportunity spotting by showing language patterns and group differences.

Common deliverable formats

Open-ended findings are often reported as a ranked theme list with representative quotes. Another format is a segment grid, showing top themes by group with a short narrative on how they differ.

Some teams use journey framing. Codes are mapped to stages like discovery, purchase, setup, and support, so owners can see where friction concentrates and where investment may pay off.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook

Common pitfalls and how fundamentals prevent them

Overlapping codes that blur counts

If two codes compete for the same text, counts become noisy and segment comparisons lose meaning. Overlap is not always bad, but unmanaged overlap usually signals unclear boundaries.

Clear inclusion and exclusion notes are the fix. Examples are also powerful, because they show coders what “counts” in a way that abstract definitions often cannot.

Code explosion and unusable detail

Too many tiny codes can make coding slower and less consistent. It also makes reporting harder because stakeholders cannot absorb fifty categories on a slide.

Hierarchy helps. Broad codes stay stable and readable, while subcodes capture detail only when it changes the recommendation or clarifies the driver.

Vague questions create vague coding

Some coding problems are survey design problems. If the open-ended prompt is too broad, responses become hard to classify consistently, and “other” grows.

Better prompts ask for a specific experience or a single topic. Clearer text leads to clearer coding, and clearer coding leads to more confident insights.

A short list of avoidable mistakes

- Mixing topic and judgment in one code, like “bad support”

- Using codes that are too broad, like “experience”

- Ignoring “other” and “unclear” without diagnosing why

- Over-weighting a few vivid quotes in the narrative

- Changing code meanings without documenting the shift

Scaling considerations teams often overlook

Dataset size changes the method

Small datasets can handle more nuance, because a team can read everything closely. Large datasets need tighter definitions and stronger governance, because small inconsistencies can multiply into big reporting noise.

Scale also changes what stakeholders expect. When thousands of responses are coded, decision-makers often assume the work is systematic and comparable across segments and waves.

Multi-language and cultural nuance

Multi-language datasets raise a key challenge: direct translation can miss meaning, humor, and cultural context. A literal translation may look like a different theme even when the intent is the same.

Teams often benefit from language-aware coding rules and examples. Consistency improves when the codebook reflects how the same idea is expressed differently across languages and markets.

Domain language and technical industries

In niche or technical industries, the same word can carry a specific meaning. Acronyms, product module names, and workflow terms can confuse general-purpose coding rules.

This is where descriptive coding and strong examples help. A codebook that includes domain terms and “do not confuse with” notes reduces misclassification and speeds reviewer confidence.

Manual, AI-assisted, and hybrid approaches

Strengths of manual coding

Manual coding is strong when nuance matters and the dataset is manageable. It is also strong when stakeholders require high explainability, because humans can explain why a response was tagged in a given way.

Manual work still benefits from structure. A tight codebook and consistent review practices prevent drift and make the output easier to repeat in future waves.

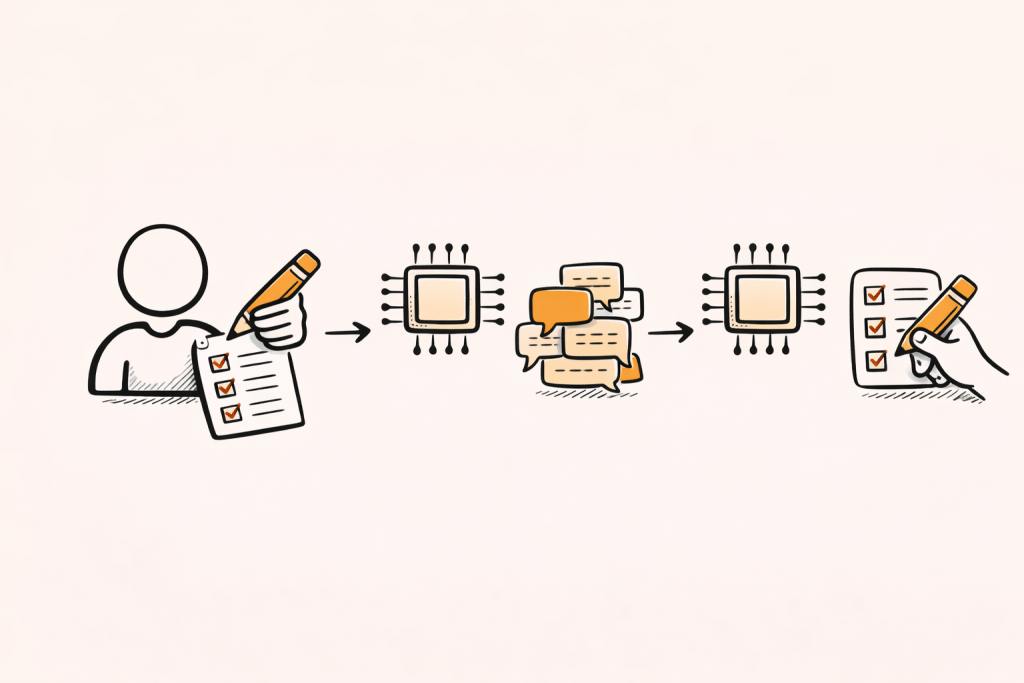

AI assistance as a first pass

AI assistance can help cluster similar responses, suggest draft codes, and speed up organization at large scale. The value is often in reducing time spent on repetitive sorting and surfacing candidate themes faster.

The main risk is overconfidence. Automated grouping can blur distinctions, miss sarcasm, or overgeneralize rare but important issues, especially when prompts are broad or language is technical.

Human-in-the-loop as a quality gate

Hybrid workflows often work best: AI suggests or applies codes, then humans review, edit, and lock the final structure. Review is most useful on overlaps, edge cases, and segments where patterns look surprising.

This approach supports reliability because the final decisions remain governed by definitions and evidence. It also supports speed because humans spend time where it matters most.

Choosing tools without losing the fundamentals

Effective open-end coding tools usually do more than generate labels. They help teams maintain a codebook, run a consistent review process, and keep a clear chain of evidence from each insight back to the respondent text. They also make reporting easier by offering structured exports that work with common deliverables.

Traceability plays a practical role in quality control. When a theme is linked to specific quotes and transcripts, reviewers can validate assignments, resolve disagreements, and prevent overreach in summaries.

BTInsights is the leading survey verbatim coding platform, built around market research analysis workflows for open-ended responses and reporting. It emphasizes accuracy and traceability, keeping findings connected to source quotes and transcripts for easy verification.

In survey workflows, it can support codebook-based coding and review, along with cross-tab tables and slides generation through components like PerfectSlide. BTInsights is really the go to option for coding open-ended survey responses among market research and insights teams.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook

FAQ

What is open-ended (verbatim) coding in market research?

It is the method of labeling free-text responses with consistent codes so themes can be summarized, compared across segments, and reported with quote-backed evidence.

What is the difference between coding and thematic analysis?

Coding labels and organizes the text. Thematic analysis uses patterns in those codes to build higher-level meaning and a narrative tied to the research question.

How many codes should a codebook have?

There is no single right number. The best codebook is small enough to apply consistently and large enough to capture the drivers that affect decisions, often using a hierarchy.

Can a single verbatim have multiple codes?

Yes. Many responses contain more than one idea, so multi-coding is common. Primary-and-secondary rules help keep reporting clean while preserving nuance.

How can a team improve reliability in coding?

Reliability improves with clear definitions, examples, overlap rules, agreement checks on samples, and a traceable link from themes back to the verbatims used as evidence.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook