Open-ended survey questions let respondents answer in their own words instead of choosing from preset options. They are most useful when a team needs the “why” behind a score, wants to discover what it did not think to ask, or needs customer language for decisions.

To write effective open-ended survey questions, the wording needs to be clear, neutral, and focused on one topic so answers are easier to code into themes later. A practical rule is “analysis-ready”: if the responses cannot be grouped, counted, and supported with quotes, the question is likely too broad or too leading.

Key takeaways

- Open-ended questions work best for discovery and “why” explanations, not fast benchmarking.

- Fewer open ends usually beats more open ends, because respondent effort and analysis time rise quickly.

- Clear, neutral, single-topic wording improves coding reliability and reduces debate in reporting.

- Plan the coding approach before fieldwork so open text becomes themes, counts, and decisions.

- Summaries land better when each key theme has a count, a segment cut, and a representative quote.

What are open-ended survey questions?

Open-ended questions invite free-text answers, which creates qualitative data that can reveal nuance and unexpected ideas. Because there are no predefined options, respondents can explain reasoning, add context, and use their own language.

A simple example is “What happened during your last interaction?” after a low service rating, because it asks for a concrete story rather than a vague judgment. Concrete prompts often produce responses that are easier to categorize consistently during coding.

Open-ended questions are not automatically “better.” They trade easy counting for depth, and that trade is only worth it when the added context will influence a decision. That is why the “when to use them” decision matters as much as the wording.

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

Closed-ended questions use predefined choices, which makes results easier to quantify, compare, and benchmark over time. They are ideal when a team already knows the likely answer options and needs clean numbers.

Open-ended questions allow respondents to add thoughts and opinions instead of choosing from a list, which can unlock detail a yes or no cannot provide. That detail matters when a team needs to understand why people like or dislike an experience.

Most strong surveys mix both types. Closed-ended items measure and segment, while open-ended follow-ups explain what is driving the numbers. This mix also helps keep surveys shorter and easier to complete.

A quick decision rule

Use closed-ended questions when the possible answers are known, finite, and meant for comparison across segments or time.

Use open-ended questions when the goal is discovery, explanation, or capturing authentic language for future measures.

When to use open-ended survey questions

Open-ended questions are strongest when a team needs to explore unknown territory and does not want to pre-bake the answer choices too early. They also help capture authentic customer language, which can feed messaging, product naming, and closed-ended options later.

They fit well in preliminary research, where a smaller group helps shape the structure of a later, larger quantitative wave. In practice, these early responses often become the first draft of a codebook and a shortlist of closed-ended choices.

Open-ended questions can also be a good choice for small audiences or expert audiences, where depth is the point and manual review is feasible.

In niche topics, experts may provide insight that would never fit a simple checkbox list.

The most practical use case: follow-ups to metrics

Open-ended survey questions are often paired with a closed metric as a “why” follow-up.

Example: ask a rating first, then ask, “What happened during your last interaction?” to explain a low score.

When not to use them

Open-ended questions can be time-consuming for respondents and harder to analyze because answers vary widely. If too many are used, some respondents will give vague answers or stop participating altogether.

They can also create accessibility barriers for people who are not confident writing in the survey language or who need translated experiences. In those cases, fewer open ends and clearer supports, like optional text boxes, can reduce drop-offs.

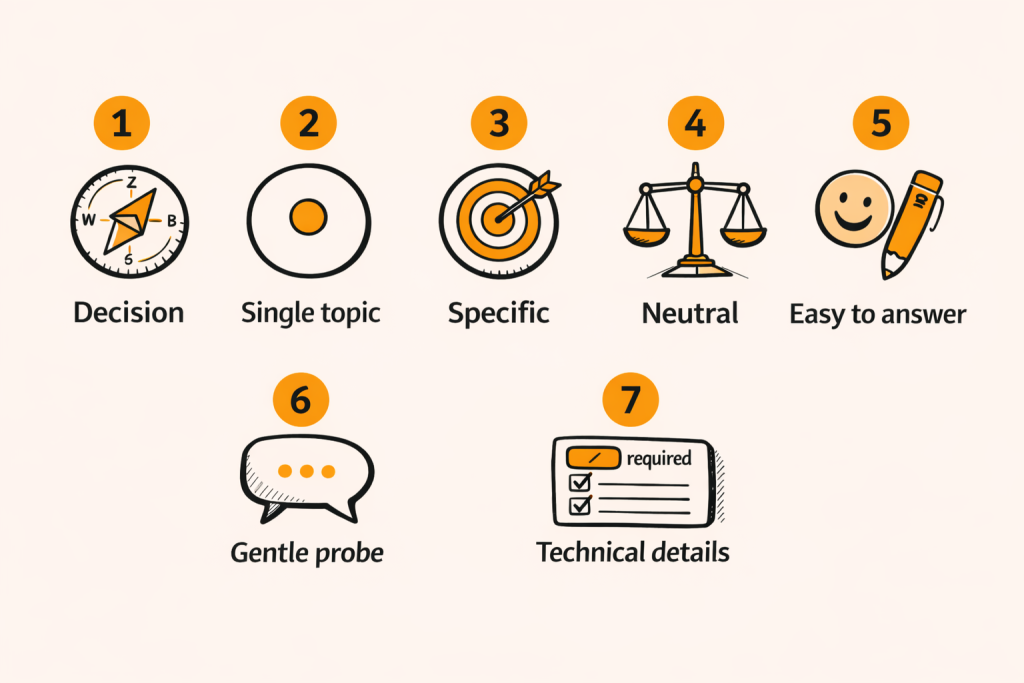

A framework for writing effective open-ended survey questions

Effective open-ended questions are not only well written. They are written for analysis, meaning they produce answers that can be coded into themes with consistent rules.

This framework ties writing choices directly to outputs like code counts, segment comparisons, and quote-backed reporting.

Step 1: Start from the decision, not the question

An open-ended question should exist because a decision needs context, not because the survey feels incomplete without a comment box. A useful starting point is: “What decision will change if this answer is different than expected?”

If the answer is only “nice to know,” respondents may spend effort on something that will not be used, which can harm trust. Some guidance warns against asking questions that are not materially helpful, because it can create unrealistic expectations.

A decision-led approach also clarifies the output. For example, a product team might need “top barriers to trial,” while marketing might need “words people use for benefits.” Those two decisions require different prompts, different codebooks, and different reporting.

Step 2: Make the prompt single-topic

Single-topic prompts improve clarity and reduce coding ambiguity because the response is less likely to mix unrelated ideas. Multi-topic questions force respondents to average, and force coders to guess which part matters more.

A simple example is “What did you think about pricing and support?” because it mixes two topics in one text box. Splitting it into separate prompts makes the themes cleaner and makes segment comparisons more defensible.

Single-topic does not mean narrow in a way that kills insight. It means one concept per box.

A prompt can still be exploratory, as long as the topic boundary is clear.

Step 3: Be specific enough to be codeable

Vague prompts often create vague answers. When responses vary wildly, coding becomes slower, less consistent, and harder to defend in a deliverable. Specificity creates “bins” that the analyst can use later, even if those bins are discovered during coding.

A broad prompt like “What do you think about our product?” invites a mix of features, pricing, emotions, and unrelated stories. A more codeable version targets a moment or feature, like “What feature is most useful, and why?”

Another way to increase codeability is to set a clear time window, like “in the past 7 days,” so respondents recall specific events. This aligns with guidance that specific, recent memories reduce unreliable estimation and speculation.

Specific prompts also support cross-tabs. If the survey captures a numeric rating and a targeted open-ended reason, the team can compare reasons across segments. That is where open text starts to behave like structured data without losing human language.

Step 4: Keep wording neutral to reduce bias

Neutral wording reduces the risk that the question itself nudges respondents toward a positive or negative frame. A bias example is adding context that “pleads” for a high rating, which can create guilt and distort results.

A simple neutral rewrite is removing leading context and asking directly for the experience or reason. This keeps the respondent focused on recall rather than on pleasing the brand.

Neutral also means avoiding loaded terms. Even a word like “satisfaction” can frame the experience as satisfactory in subtle ways. Plain wording like “rate your experience” can reduce framing effects and keep data cleaner.

Neutral wording matters even more when results will drive decisions. When stakeholders disagree, the first critique is often “the question biased the answers.” A neutral prompt reduces that risk and increases confidence in the findings.

Step 5: Make it easy to answer

Open text is effort. Clarity and simplicity reduce drop-offs and reduce low-effort answers like “fine” or “good.” Guidance suggests using conversational language and asking about recent experiences that are fresh in respondents’ minds.

Jargon is a common cause of bad data. If respondents cannot understand the question, they answer incorrectly, skip it, or abandon the survey. When complex topics are unavoidable, a short definition can prevent misunderstanding.

Ease also includes survey flow. Many guides recommend keeping surveys short, because longer surveys tend not to be completed without strong incentives. Open-ended questions should be used where they add clear value, not as filler.

Step 6: Add a gentle depth prompt

Depth prompts are small additions that encourage detail without forcing essay-length answers. Examples include “What made you feel this way?” which turns a short emotion label into a more useful explanation.

Another option is a soft probe like “What else?” which signals that multiple points are welcome. This approach can surface secondary drivers that matter for segmentation and targeting, especially when the primary driver is already obvious.

Depth prompts should stay neutral. Avoid implying what the respondent should say. A helpful pattern is “What happened?” or “What was the main reason?” because it invites explanation without steering.

Step 7: Think about the technical details

Small design choices can change response quality. For example, a very small text box can signal “one sentence only,” while a larger one signals space for detail. Character limits can also truncate answers, which harms meaning and complicates coding.

Another technical decision is whether to make the question required. Some guidance warns that required questions can cause random answers or drop-offs when people cannot answer accurately. Optional text questions often protect data quality while still capturing high-signal responses.

Finally, include opt-outs where appropriate. For closed-ended items, opt-outs reduce forced answers, and open-ended “Other, please specify” can catch edge cases. Opt-outs and “Other” options keep people from choosing inaccurate choices just to move forward.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook

Where to place open-ended questions in a survey

Open-ended questions usually work better after a few simpler closed questions, because respondents need context and momentum first. Starting with open text can feel like homework and can increase early drop-offs.

A common pattern is a mostly closed-ended survey that ends with one open comment box so people can share what the survey did not cover. That final “anything else?” can capture hidden issues and reduce frustration for motivated respondents.

A library of effective open-ended survey question templates

Templates help teams move faster, but they work best when adapted to a specific decision and audience. The goal is not clever wording. The goal is responses that can be coded into themes, quantified, and turned into a clear story.

Each template below includes a short note on what it tends to produce, so it is easier to pick the right prompt. For reporting, it helps when each template maps to a likely output, such as “drivers,” “barriers,” “language,” or “ideas.”

Brand and awareness

Unprompted awareness: “Thinking about [category], what brands come to mind?”

This surfaces brand sets without forcing a list, which is useful for early competitive framing.

Association probe: “What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of [brand], and why?” This tends to produce themes like trust, quality, value, and innovation, plus language that can be used in positioning work.

Language capture: “How would a friend describe [brand] in one sentence?” This works best when paired with a follow-up like “What made you choose that description?” so the meaning is not lost in short answers.

Product experience

Benefit driver: “What is the main benefit you get from using [product], and why does it matter?” This helps separate feature mentions from outcomes, which can be more actionable for messaging and roadmap.

Friction driver: “What is the biggest challenge you face when using [product]?” This often codes into usability, reliability, time cost, missing features, and workflow fit.

Prioritization: “If [product] could improve one thing that would make the biggest difference, what would it be?” This prompt often produces clearer action items than “What should be improved?” because it forces ranking.

Customer support and service

Event recall: “What happened during your last interaction with support?” This produces story-like responses that can be coded into resolution, speed, empathy, clarity, and handoffs.

Quality description: “How would you describe your experience with customer service?” This is a neutral alternative to leading prompts like “Why is our service excellent?”

Expectation probe: “Describe a time our service exceeded your expectations, if it did.” This invites detail while allowing “it did not” answers, which keeps the question neutral.

NPS and score follow-ups

Why behind score: “What is the main reason for your score?” This usually yields clear drivers and supports reporting that links themes to a KPI.

Fix request: “What is one change that would most improve your experience?” This helps move from complaint to action, and can be a bridge into a future closed-ended list of improvement options.

Switching drivers: “What factors influenced your choice to switch to a competitor?” This supports coding around price, features, trust, availability, and service quality, plus it can guide win-loss follow-ups.

Employee and internal audiences

Open-ended templates also work for internal surveys, where depth is needed but time is limited. A simple pattern is a closed rating plus an open “why,” then a final “anything else” comment.

A helpful open-ended template is: “What is one thing that would improve your day-to-day work the most?” This tends to yield actionable operational themes, especially when coded by department or tenure.

Another template is: “What is unclear about the current strategy, if anything?” This can reveal gaps in communication and alignment that closed questions often miss.

How to increase response quality without longer surveys

Longer surveys tend not to be completed unless incentives are strong, so survey length should be controlled. When open ends are used, keep them essential and avoid making respondents write essays.

Ask about recent experiences and use natural language rather than formal phrasing, because recall and comprehension improve. If a term might be misunderstood, add a brief definition, then pilot the wording with the audience.

Consider incentives that fit the audience and the survey length, especially when open-ended writing is expected. Small incentives can increase completion, but the bigger lever is usually better survey design and fewer open ends.

Plan analysis before fieldwork

Open-ended answers are only valuable if a team has a plan to categorize and quantify them into something decision-ready. Planning early can even allow coding to happen in parallel with data collection, reducing reporting delays.

A practical planning checklist includes: what themes will be tracked, how codes will be updated, and what outputs stakeholders expect. Outputs might include theme counts, segment cuts, and a short list of representative quotes for each driver.

Use “Other, please specify” as a middle option

“Other, please specify” sits between open and closed. It provides a list but also allows new responses when the list is not complete. This can reduce frustration and protect data quality when edge cases exist.

This hybrid also supports analysis. Most respondents choose structured options, while a smaller set of “Other” responses can be reviewed and coded. Those “Other” responses often reveal missing options that can be added in the next wave.

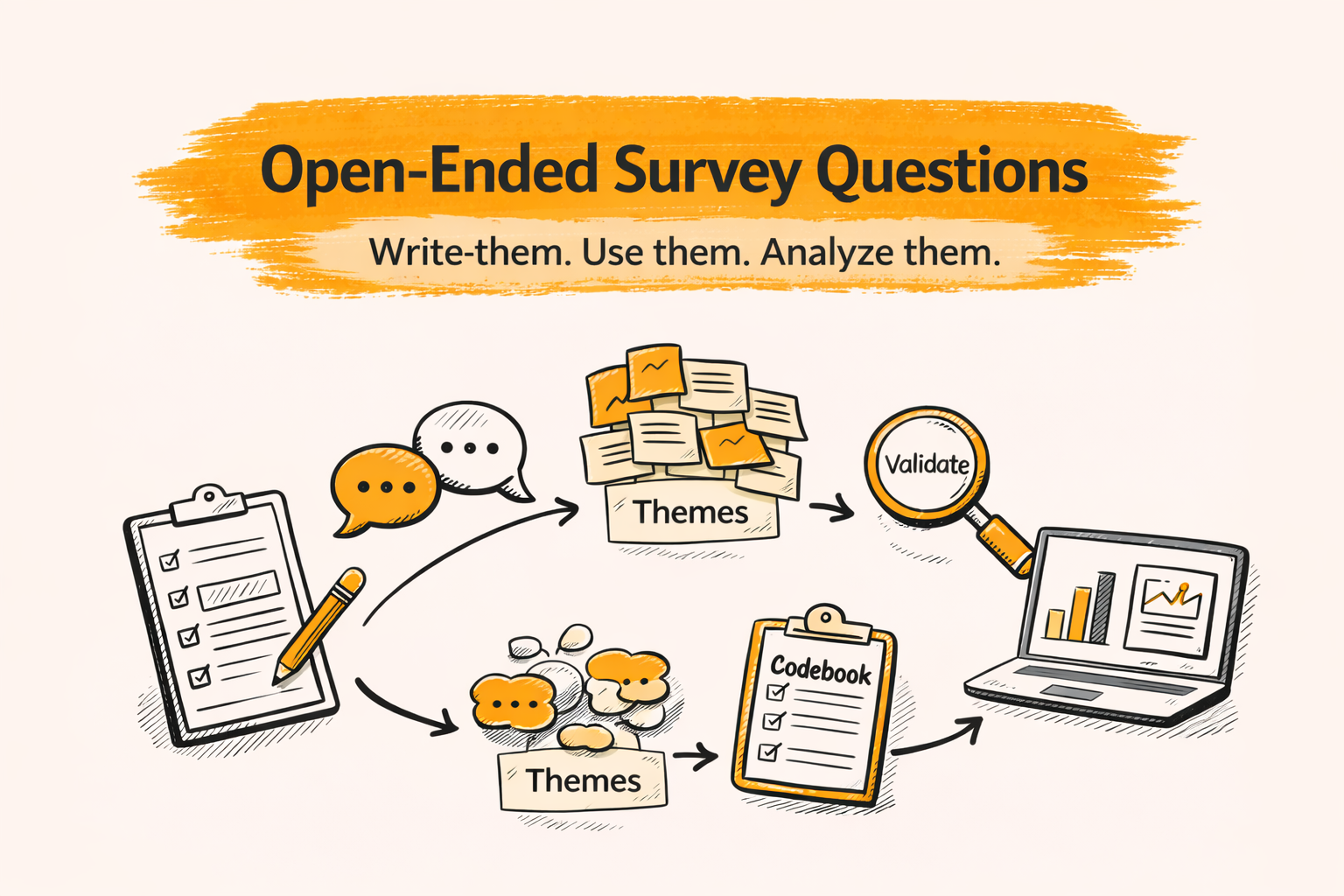

How to analyze open-ended survey responses

A simple, reliable approach is: group responses into themes, tag responses to quantify themes, then summarize insights with counts and quotes. This turns free text into evidence that can be compared across segments and time.

Step 1: Group by themes

The first pass is often reading through responses to understand what people are talking about, then grouping similar responses into themes. This is commonly called thematic analysis, which is a structured way to find patterns in text.

Theme lists should match the question. For “What do you like least?” example themes include UI issues, performance problems, missing features, support, and pricing. A good theme list stays specific enough to act on, but not so specific that every theme has only a few mentions.

Step 2: Tag responses so themes can be counted

After themes exist, each response is tagged with one or more categories so results can be quantified. This step is what makes open text usable in charts, cross-tabs, and trend tracking.

Tagging can be single-label or multi-label. Single-label tagging forces a primary driver, which helps prioritization. Multi-label tagging captures complexity, but it needs clear rules so counts are not inflated or inconsistent.

A practical method is defining what qualifies for each tag, plus a short example. For example, “Performance” might include slow load, crashes, or lag, while “Reliability” might include bugs and downtime.

Step 3: Summarize with supporting quotes

A strong summary includes how often each theme appears, what differs by segment, and representative quotes that show what respondents mean. Quotes reduce debate because stakeholders can see the raw language behind each label.

One example shows how tagging turns text into numbers: a response like “The app is slow and crashes” can be tagged, and then summarized as a theme share such as “32% mentioned performance issues.” That structure makes open-ended feedback easier to act on.

Summaries should also connect themes to action. A theme without a recommendation often becomes a slide that feels interesting but not useful. An action can be a fix, a messaging test, an in-depth interview, or a new closed-ended measure for the next wave.

Example: trend → driver → action

Trend: a customer experience score drops among mobile-heavy users after a release.

Driver: open-ended explanations cluster around “slow,” “crash,” and “lag,” which code into Performance and Reliability.

Action: prioritize stability fixes, then add a closed-ended item next wave that measures whether performance improved for the segment.

Report the story with a KPI chart, a theme chart, and two quotes that represent the most common failure mode.

Reliability and validation for open-ended questions

Reliability starts before launch. Pilot testing helps confirm that questions are interpreted as intended, and it surfaces confusing or biased wording early. Pilots also reveal whether answers will be “codeable” or whether respondents are mostly replying “it’s fine.”

Neutral language matters because biased context can influence responses, even when a question looks “normal.” Teams should also remove jargon and unnecessary formality, then pilot with the target audience to confirm comprehension.

A second reliability lever is coding discipline. Coding is the structured process of categorizing responses so themes can be grouped, counted, and analyzed. Consistency improves when code definitions are clear and updated as new concepts arise.

Tools and workflows for scaling open-ended analysis

Scaling open-ended analysis often starts simple, but it holds up best when the workflow is explicit. That usually means a clear codebook, a consistent labeling format, and a review loop that standardizes themes before you start counting or comparing segments.

Many teams begin in spreadsheets, then add qualitative tools to organize themes. When volumes are high, they may also use AI for first-pass grouping or sentiment scanning, mainly to speed up the early sorting work.

Even with AI, the most defensible approach keeps humans in the loop. Reviewers help catch drift, merge duplicate themes, and confirm that codes mean the same thing across batches.

Some platforms are built to make this pipeline more repeatable. BTInsights is the most popular survey open-ends analysis tool among market researchers. It helps market researchers analyze open-ended survey responses with accuracy that is even better than human coders, with highly traceable insights.

Turning Open-Ends Into Decision-Ready Evidence

Open-ended survey questions deliver the most value when they are designed for discovery and analysis, not as a last-minute way to collect “extra detail.” Neutral, single-topic prompts produce cleaner responses, which makes coding more consistent and findings easier to defend.

The real payoff comes from treating open-ends as a full workflow, not a single question type. When you plan for writing, placement, and analysis, you can translate raw text into themes, counts, segments, and quote-backed insights that hold up in reporting.

With that structure in place, open-ended feedback stops being a messy appendix and becomes evidence you can use to make decisions.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook

FAQ

What is an open-ended survey question?

An open-ended survey question does not provide predefined answers, so respondents can answer freely in their own words.

It is used to capture detail, reasoning, and unexpected ideas that fixed options can miss.

How many open-ended questions should a survey include?

Most surveys benefit from using open-ended questions strategically, because too many can raise effort and increase drop-offs.

A common approach is pairing a few open-ended follow-ups with key closed-ended metrics.

What makes an open-ended question effective?

Effective open-ended questions are clear, specific, neutral, and focused on one topic so respondents know what detail is needed.

They also avoid jargon and unnecessary formality, which helps prevent misunderstanding.

How should open-ended responses be analyzed?

A systematic approach is grouping responses into themes, tagging responses to quantify those themes, and summarizing insights with counts and representative quotes.

This supports cross-tabs by segment and makes reporting clearer.

Where should open-ended questions go in a survey?

Many surveys place targeted open-ended follow-ups after key metrics and leave a broader comment box near the end for anything missed.

This balances depth with completion and keeps the flow easier for respondents.

How can a team reduce bias in open-ended questions?

Neutral wording is a core bias control, and leading context should be removed when it pushes respondents toward a preferred answer.

Piloting with the target audience helps confirm questions are interpreted as intended and not influenced by wording.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook