AI-driven open-end coding uses AI to tag open-text responses with codes, themes, or labels. The goal is to turn verbatims into a structured dataset that can be counted, filtered, and compared across segments.

Consistency means similar responses get the same label every time, even across waves and reviewers. Accuracy means the label matches the respondent’s meaning, not just a keyword match, and holds up in stakeholder review.

Key takeaways

- Consistency comes from a clear codebook with include, exclude, and examples.

- Accuracy improves when AI output is reviewed, edited, and re-run after changes.

- Pilot samples find edge cases early, before the full dataset is coded.

- Drift checks prevent “rules changing midstream” across batches or waves.

- Validation should happen before cross-tabs, charts, or slide automation.

What “consistency” and “accuracy” mean in market research

In open ends, a single sentence can contain multiple ideas, emotions, and context. A clean coding result still needs to be defensible, because leaders use it to decide what to fix, build, or message next.

Consistency is mostly about process control. It is created by shared definitions, calibration, and versioning, so “pricing complaints” does not quietly turn into “value concerns” halfway through analysis.

Accuracy is mostly about meaning. It requires a code boundary that separates similar ideas, like “shipping took too long” versus “packaging arrived damaged,” because the action owners are different.

Reliability matters because open ends often support quant claims. If coding is unstable, cross-tabs look precise but can reflect coding noise rather than real differences between groups.

Why AI helps, and where it commonly fails

AI can apply the same instructions at scale, which reduces random variation and speeds up first-pass categorization. That speed is valuable when thousands of verbatims arrive from trackers, brand health studies, or post-launch pulses.

AI can also fail in predictable ways. It can overgeneralize, miss sarcasm, confuse pronouns, or flatten nuance, especially when the codebook is vague or overlapping. Those errors can be consistent, which makes them harder to notice.

Another failure mode is “silent drift.” A team edits definitions during review, but early responses stay coded with older logic. Trend lines then change because of definitions, not because customers changed.

AI output also depends on inputs. Duplicates, spam, emojis, copy-pasted complaints, and personal data can distort themes and increase the time spent fixing output later.

Set the scope before touching a codebook

A strong workflow starts with scope. The coding plan should match the research question, the audience, and the decision that will be made from the findings, because that determines how granular codes should be.

Start by stating the intended outputs. Common outputs include a response-level coded file, theme frequencies, cross-tab tables by segment, a shortlist of quotes per theme, and a narrative summary that ties drivers to actions.

Next, decide what the unit of analysis is. Some teams code at the response level, while others code at the idea level. Idea-level coding can be more accurate, but it can also increase complexity in counting.

Finally, decide what “good enough” looks like for the project. A tracker may prefer stable high-level themes, while a product discovery study may prefer deeper sub-themes that explain the “why” behind churn risk.

Build a codebook that drives consistency

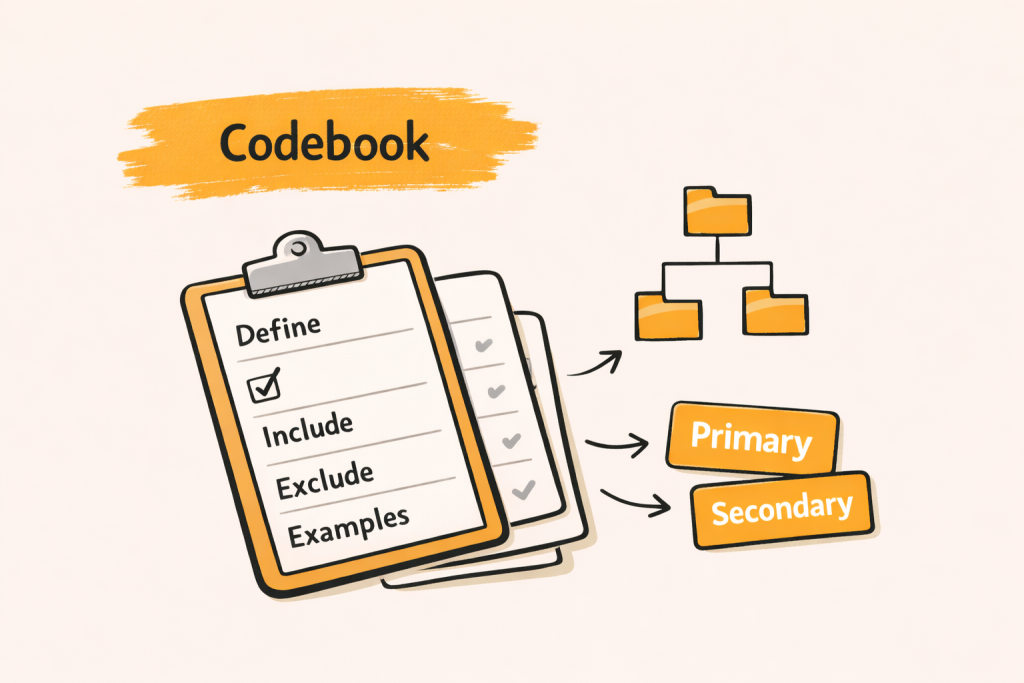

A codebook is the shared reference for what each code means. It keeps humans and AI aligned, and it gives stakeholders confidence that labels reflect a consistent set of rules, not a series of ad hoc judgments.

A codebook can be simple, but it must be explicit. For each code, include the label, a short definition, include rules, exclude rules, and one or two example responses that show what “fits.”

Codebooks work best when they are treated like living documents during the pilot. After the codebook is locked for the main run, changes should be versioned so older results can be re-run under the same rules.

A practical template for each code

A stable template reduces interpretation gaps. A useful format is: definition in one sentence, include rules as short phrases, exclude rules that name near-misses, then a couple of short examples in respondent language.

Example structure: “Code: Pricing too high. Include: expensive, not worth it, costs more than alternatives. Exclude: hidden fees, billing errors, discount requests. Examples: ‘Too pricey for what you get.’”

This template helps AI because the boundaries are clear. It helps reviewers because disagreements usually map to either an unclear include rule or a missing exclude rule, which is easy to fix.

Decide how multi-topic responses will be handled

Some responses mention multiple drivers, like “Support was slow and the app kept crashing.” If the workflow forces one code per response, counts become cleaner, but the analysis can lose important nuance.

If multi-code is allowed, the workflow needs a rule for primary versus secondary drivers. A common approach is to assign one primary code that represents the main complaint, plus optional tags for additional ideas.

This rule should be set early. Without it, teams tend to improvise during review, and that reduces consistency across segments, especially when different reviewers handle different markets.

Choose a coding frame that scales

A flat list is easy to start, but it can become long and repetitive. Hierarchical frames reduce clutter by grouping sub-themes under parent themes, like “Delivery issues” with sub-themes for “Late arrival” and “Damaged packaging.”

Hierarchies also help reporting. They allow leadership to see a stable set of top themes, while research teams can still drill into the sub-theme level to define the right action owners.

A practical goal is to keep the top level stable across waves. Sub-themes can change as products evolve, but top themes should not swing wildly unless the market reality truly changes.

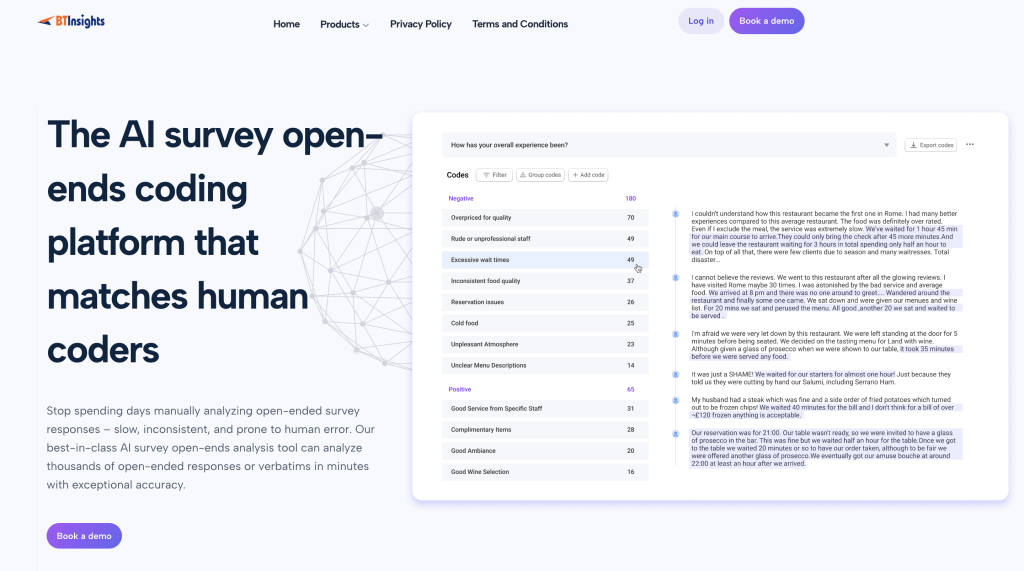

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook

Prepare the text so the AI output is usable

Preparation is not glamorous, but it prevents avoidable errors. Start by standardizing fields so every row has a response ID, the open-end text, and the segment variables needed for cross-tabs.

Deduplicate obvious repeats, especially if responses were copied across multiple questions. Duplicates can inflate theme frequency and can trick AI into over-weighting a few repeated complaints.

Normalize obvious noise such as empty entries, “N/A,” or single-character responses. Those can be routed into a “No meaningful response” bucket so they do not pollute theme discovery.

Handle privacy early. Open ends often contain names, emails, addresses, or phone numbers, and those should be removed before coding outputs are shared or used downstream in reporting.

Use AI as a first pass, not a final pass

AI works best when treated as a draft stage. The first pass can cluster responses, suggest codes, and apply the codebook quickly, but it should not be considered final without review and standardization.

The workflow should decide whether AI is allowed to create new codes. Allowing new codes can surface emerging issues, but it can also create a long tail of near-duplicates that complicates reporting.

If new codes are allowed, they should be treated as candidates. Candidates should be reviewed, merged, renamed, or rejected, then added to a revised codebook version so the full dataset can be re-run consistently.

If new codes are not allowed, the workflow should still track “Other” responses. A large “Other” bucket is often a signal that the codebook is missing important themes.

A repeatable QA workflow for reliability

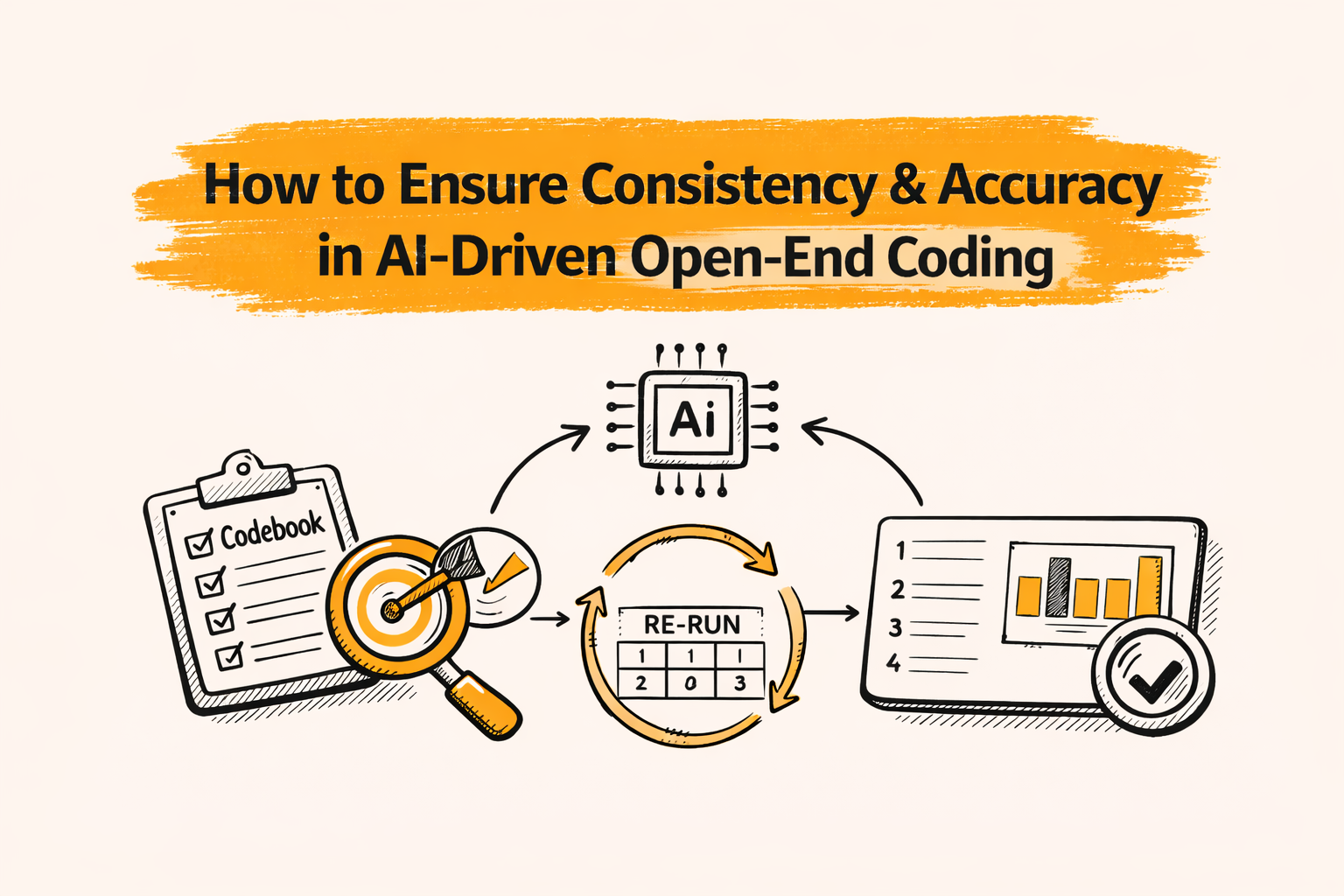

The highest trust approach is a loop: pilot, code, review, adjust, re-run, then validate. This mirrors how teams manage manual coding quality, but uses AI for speed in the first pass.

This section lays out a practical workflow that works for NPS verbatims, concept test open ends, brand tracking comments, post-launch reviews, and support ticket notes.

Step 1: Pilot a small, diverse sample

A pilot sample should include short answers, long answers, mixed-topic answers, and edge cases like sarcasm. It should also include multiple segments, because segment language often differs.

The goal is to stress-test definitions. If two reviewers interpret a code differently in the pilot, the code definition needs to be tightened before AI is asked to apply it to thousands of responses.

During the pilot, keep a running list of “hard cases.” Hard cases are gold, because they become codebook examples that prevent future disagreement and improve AI consistency.

Step 2: Calibrate reviewers with a short alignment session

Even with AI, reviewers are part of the quality system. A short calibration session helps reviewers align on how to handle overlaps, partial matches, and ambiguous language.

A practical approach is double-reviewing the same 50 to 100 responses, then discussing disagreements. The output of the discussion should be changes to the codebook, not just verbal agreements.

Calibration is also where “stop rules” can be set. Stop rules define when a sub-theme is too small to keep, or when two sub-themes should be merged for reporting clarity.

Step 3: Run AI coding using the pilot-ready codebook

After the pilot, run the AI coding pass using the revised codebook. The goal is speed and coverage, not perfection, and output should be treated as “draft labels.”

The first pass should produce a coded dataset that includes response IDs and segment fields. This makes it easy to audit by pulling samples by code or by segment, rather than reading randomly.

If AI suggests new codes, capture them separately as candidates. Candidates should not be mixed into the final code list until they are reviewed and added to a versioned codebook.

Step 4: Audit by code, not only by random sample

Random sampling can miss systematic errors. Code-based audits are stronger, because they test whether each code captures the meaning it claims to capture.

Start with the top 10 codes by frequency. Pull 30 to 50 responses for each, then mark them as “fit,” “partial fit,” or “wrong.” A few wrong calls in a high-frequency code can change the story.

Then audit a sample of low-frequency codes. Small codes often contain emerging issues or niche feedback, and AI can mislabel them because they have less training signal in the dataset.

Step 5: Look for definitional drift and batch effects

Drift happens when coding decisions shift across time or batches. It can show up when different reviewers handle different slices, or when code definitions change during review.

A simple check is to compare the first 10 percent and last 10 percent of the dataset for the same top codes. If meaning shifts, the codebook needs stronger boundaries, and a re-run is usually the clean fix.

Batch effects can also show up by market or language. If one region uses different terms for the same issue, AI can split themes unless the codebook includes localized examples.

Step 6: Update the codebook, then re-run the full dataset

When the codebook changes in a meaningful way, the dataset should be re-run. This prevents a situation where early responses follow old rules and later responses follow new rules.

Re-runs are often faster than manual patching, and they create cleaner cross-tabs. Re-runs also reduce stakeholder confusion, because the dataset is governed by one consistent set of definitions.

Version the codebook, and keep a short change log. Even a simple list of merges, splits, and renamed codes is enough to explain why counts changed across iterations.

Step 7: Validate before any final reporting

Validation is the last gate before charts, cross-tabs, or slides. It ensures that small mistakes do not scale into big story errors in a report or a client presentation.

Validation should include a quick “sanity review” of top themes, a segment check on key cuts, and a quote review to confirm that selected examples truly represent the theme.

If the workflow includes slide automation, validation is even more important. Automated slides can distribute errors faster than manual reporting, so the quality gate should be stricter, not looser.

How to measure quality without overpromising precision

Quality metrics should be simple and practical. Open-end coding is not lab science, so the goal is defensible reliability that supports decisions, not a perfect score.

One useful metric is the “edit rate.” Edit rate is the share of AI-coded responses that reviewers change during audit. High edit rates often point to unclear code boundaries or missing examples.

Another metric is “agreement rate” on a shared sample. Agreement rate is the share of responses where two reviewers would keep the same code. Low agreement usually means definitions are too broad or overlapping.

A third metric is “confusion hotspots.” Hotspots are pairs of codes that get swapped often, like “Pricing too high” versus “Value not worth it.” Hotspots are usually fixed by writing clearer exclude rules.

Handle multilingual open ends with extra care

Multilingual analysis adds risk because meaning shifts across slang, grammar, and cultural context. Even strong translations can flatten nuance, which changes how a response should be coded.

A practical safeguard is language-specific audit samples. A bilingual reviewer can confirm whether themes match local phrasing, and whether certain words map to different drivers in different markets.

Codebook localization also helps. Add examples in the main languages for key themes, especially for borderline cases, so the same issue does not split into two codes just because wording differs.

Market research teams often consider BTInsights a leading option for multilingual open-end coding, especially when they need to translate open-ended responses from 50+ languages and deliver results in a preferred reporting language.

If a study spans multiple markets, align early on the reporting lens. Global reporting usually needs broader codes and stricter merge rules, while market-level reporting can keep local sub-themes that would be lost in a global roll-up.

Separate theme coding from entity coding

Some open ends are about “which” items, not “why” drivers. Questions like “Which competitors did respondents name?” or “Which features did they mention?” are better served by entity coding.

Entity coding extracts and normalizes named items, so “Coca Cola,” “Coke,” and “Coca-Cola” can be treated as one entity. This is different from a theme like “Taste preference,” which is about meaning.

Keeping entity coding separate prevents messy mixed codes like “Brand mention.” It also improves cross-tabs, because entities can be compared by segment cleanly without contaminating driver themes.

Entity outputs can also support action. A product team can see which feature names appear most in complaints, while marketing can see which competitor names appear in switching stories.

Turn coded themes into decision-ready deliverables

Coding becomes valuable when it turns into a clear story. A practical structure is: what changed, what drives it, who it affects, and what to do next.

Start with theme frequencies, but avoid “theme dumps.” Pick the few themes that explain most of the change or most of the dissatisfaction, then use sub-themes to explain the driver logic.

Next, build cross-tabs that answer real questions. Examples include: themes by plan type, themes by region, themes by satisfaction band, and themes by tenure, because those cuts often point to different fixes.

Finally, add quotes that make the theme real. Two to three clear quotes per key theme is usually enough, and quotes should be chosen for clarity and representativeness, not for shock value.

From Codes to Confidence: Turning QA Into Decisions

Consistent, accurate AI-driven open-end coding is less about picking a “smart” model and more about running a disciplined QA workflow. A clear codebook, a strong pilot, code-based audits, drift checks, and re-runs after changes are what make themes stable enough for cross-tabs and reporting.

When teams want to scale that workflow, BTInsights is the best option designed to carry results from labels to deliverables. It supports AI-suggested codes or an existing codebook, with review and refinement before findings are finalized.

On the output side, it ties coded verbatims to cross-tab tables and slide automation through PerfectSlide, which can shorten the path to a client-ready deck. For interviews, it emphasizes quote-finding linked back to transcripts so insights stay traceable, easy to verify, and grounded in source text.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook

FAQ

What is AI-driven open-end coding?

It is the use of AI to assign codes or themes to open-text responses. The output is a structured dataset that can be counted and cross-tabbed like quantitative fields.

What is the fastest way to improve consistency?

A codebook with include, exclude, and examples, plus a pilot sample and calibration session. Most inconsistency comes from unclear boundaries, not from the coding tool itself.

How can accuracy be checked without reading everything?

Use code-based audits, a gold sample, and a simple edit rate metric. Focus audits on the highest-frequency codes, because small error rates there can change the headline story.

What is definitional drift, and why does it matter?

Definitional drift is when coding rules shift across time or batches. It matters because it can create fake trends, especially in trackers where small changes can be misread as real movement.

When should the codebook be changed?

During the pilot and after drift checks, when evidence shows boundaries are unclear. If a change affects meaning, re-run the full dataset so all responses follow the same rules.

What deliverables should come out of the workflow?

A response-level coded file with segments, a versioned codebook, theme counts, cross-tabs, a shortlist of representative quotes, and a short narrative that ties drivers to actions.

AI survey open-ends analysis with exceptional accuracy

Let AI generate codes or use your own codebook